The Accountability Ecosystem in Kenya Today

Understanding the current Kenyan media landscape, and its strength as a public gatekeeper and watchdog, requires examining the strength and character of media’s relationship with the other “accountability ecosystem” constituents: Government, Citizens, and Civil Society. As this study attempts to show, interactions between media and these constituents create pressures and incentives, which influence media’s ability to provide independent, unbiased reporting on issues of public interest. This report analyzes these pressures, as well as media’s responses, to understand how different factors influence media’s ability to produce robust, critical, and independent journalism.

In the first section, we examine the Media itself to explore how financial struggles are forcing establishment media companies to downsize their newsrooms, which in turn has contributed to a decline in the quality of reporting and the capacity of journalists. We also look at gender imbalances within Kenya’s media, which has implications for the future leadership of women in media organizations and the representativeness of reporting. We then explore the role of the other three constituents—Government, Citizens, and Civil Society—and the pressures and incentives they bring to bear on Kenyan media’s ability to produce quality reporting in the public interest. We assess the impact of these pressures through a Free and Fair Scale, which illustrates whether a particular incentive or pressure is contributing to a stronger media landscape, or weakening it. For example, a decline in revenue for establishment media has forced staff layoffs, reducing the media’s capacity to produce sustained reporting on important issues, while leaving many journalists economically vulnerable. This receives a negative score on the scale, because the media now has reduced capacity to fulfil its mandate as a public watchdog.

We define civil society broadly, encompassing community-based organizations, religious organizations, and other non-governmental and non-commercial groups.

Constituent 1: Media

Kenyan media faces powerful political and commercial challenges. Media organizations have had to contend with declining commercial advertising revenue as new entrants have led to a crowded landscape. This audience fragmentation in turn has reduced the market share for the major media companies. For example, the shift to digital television in 2015 introduced significant new competition among television channels. Kenyan media is also still trying to figure out how to cope with drastic cuts in government advertising stemming from a government directive in 2017 limiting the publishing of ads and public notices to the government’s own “MyGov” publication.

In this section, we look closely inside Media itself, and the pressures and incentives that journalists and editors face.

Pressures and incentives

Across all mediums, most media companies have struggled to find appropriate business models within a changing economic and technological environment. As a consequence, leading companies have radically downsized, starting in late 2015, with the onset of digital television. The Nation Media Group, for instance, closed two radio stations (opting instead for an online stream) and merged two television stations. Most establishment media companies have gone through several rounds of layoffs. In late 2017 and early 2018, both The Nation Media Group and The Standard announced another round of substantial layoffs.

Declining revenue limits journalists’ capacity

The profession as a whole in Kenya has suffered a noticeable decline, due to the economic pressures and government attacks.

With financial troubles fundamentally changing newsrooms, respondents were eager to identify new, sustainable funding streams and models. Like media companies around the world, Kenyan media are still struggling to monetize online audiences and make up for lost ad revenue. Commercial advertisers have started to move their money to online ad services such as Google Adwords. At the same time, establishment media have had to contend with a drastic decline in government ad revenue. The government has reportedly ordered government departments to only advertise in the government’s MyGov publication. AFP reported that the government had been spending upwards of USD 19 million a year on private advertising, which the establishment media stand to lose. At the same, the government has allegedly failed to pay debts of almost USD 10 million to Kenyan media houses for advertising it had already run. In turn, establishment media’s profitability has dropped significantly. In 2016, profits across the industry reportedly shrank by almost USD 15 million. They have since gone through multiple rounds of layoffs of editors and journalists, retrenching hundreds of staff.

Without staff journalists, newsrooms increasingly depend on freelance journalists and correspondents to produce content at a lower cost. In fact, one study found that approximately 80 percent of journalists are employed as correspondents. Correspondents, who typically have contracts to produce a certain number of stories a week, and freelance, paid-per-story journalists receive significantly less payment than staff. They also do not receive benefits and typically have less experience and/or training. Staff journalists, on the other hand, are generally paid a salary, which, as one correspondent for The Standard notes, “allows for more time to work on quality stories.”

In addition to pay, there are other benefits to working as staff journalists. A Standard correspondent noted that working in the newsroom as staff allows “a lot of face time with editors, which helps get stories in the paper.” The implication is that without this face time, it is harder to get the necessary feedback and support to get stories published, which impacts whether correspondents and freelance journalists will be paid at all. This particular Standard correspondent was contracted to produce two stories per day, but tried to produce up to four, because he was unsure what the newspaper would actually print, which then impacted whether he would be paid at all. Payments for a story can range from as low as USD 20 to 1000, depending on the perceived value of the story. Monthly pay for freelancers may be “as little as USD 100 per month.”

However, even in newsrooms, journalists are not receiving the support they need. A culture of mentorship, once an important source of professionalization amongst journalists, has mostly disappeared. In reference to the declining quality of reporting in Kenya, an investigative journalist explained, “a lot of this is because of a lack of mentorship. This is no longer embedded in the culture of news reporting. Before, editors would take time to explain to their staff why a story was good or bad. They would take the time to brief them before they went out to get a story; now, not so much.” He went on to say that, “some of this is because of the level of experience editors have now. While it used to be 10 plus years of experience, now it has gone down to about two or three.”

This shift to low-wage, contract journalism has, in the words of one respondent, resulted in the “juniorisation” of the newsroom. Without resources, mentorship, or professional support, young journalists struggle to produce high quality reporting. In fact, most respondents cited journalistic capacity as one of the biggest challenges to strong independent media. Even journalists themselves acknowledge their own capacity issues. A county-level correspondent said, “As a correspondent, I feel held captive. I have very little opportunity for professional growth. Correspondents are expected to cover county issues but we are not taught how to do so.”

Need for targeted training

Given the well-known capacity gaps of professional journalists and editors, many respondents lamented a lack of hands-on training within the education system. A current media trainer and experienced journalist explained that “many universities offer journalism courses, but they offer theoretical skills and not practical. This is a shortcoming and hindrance of the current crop of journalists being churned out.”

A number of actors are working to fill this gap: The Media Council of Kenya offers trainings, as do some civil society groups. A few international NGOS are providing mentorship and training. However, at least a few respondents referred to journalists as “overtrained,” even though capacity continues to remain an issue. The criticism frequently heard was that these trainings, often referred to as “helicopter trainings,” were seen to be designed based on donor directives, rather than a thorough understanding of journalists’ needs. Media trainers cited instances of journalists failing to complete trainings or applying the new skills they had acquired. Journalists, for instance, who receive training on covering government finance, were not observed actually reporting on related issues.

Women face challenges in newsrooms

For Kenya’s female journalists, the constraints multiply. Although recent data on the percentage of female journalists in Kenya is unavailable, a 2011 study found “women journalists are greatly under-represented in the Kenyan news organizations surveyed, with men outnumbering women more than 2:1. Women’s participation is most noticeably low in governance and middle management levels, as well as in production and design.” Respondents for our research highlighted multiple barriers that include discriminatory hiring practices, widespread sexual harassment in the workplace, and increased risks of online attacks.

Beyond affecting editorial decision-making on the issues covered, this gender imbalance is reflected in the ways stories are told. A 2015 report found men “10 times more likely than women to be a news source actor”, illustrating the lack of representativeness in voices and perspectives that are sought, legitimized, and used.

However, Kenyan communication and journalism schools are flush with aspiring female journalists—in some cases, they outnumber male students. Yet newsrooms remain heavily male-dominated. As one civil society respondent working on gender and media issues noted, “there are lots of female communication or journalism students, but they aren’t going to or staying in the newsroom. There is this prevailing notion that the newsroom is for men.” This lack of female journalists is consistent with 2015 research by the Media Council of Kenya, which examined 912 news articles and found only 7 percent were written by women.

The prevalence of sexual harassment, both within and outside the newsroom, may be one reason preventing female journalists from advancing in their careers. Researchers heard frequent reports of women journalists subjected to sexual harassment in the workplace, some of which have recently been reported on in the Kenyan press. Such harassment is frequently compounded online, mirroring a well-documented, global trend of online harassment toward female journalists. In Kenya, a 2016 survey found 75 percent of female journalists to have experienced digital harassment during the course of their work. Female journalists are also perceived, in some cases, to be judged more harshly than their male colleagues, and face increased risk of public threat and intimidation. One respondent cited an example of a female sports announcer who is regularly subjected to fierce online attacks, most notably when her predictions are wrong.

Yet Kenya’s female journalists continue to work to overcome these barriers, even as these forces narrow the critical pipeline of their rise through media ranks.

How individuals respond

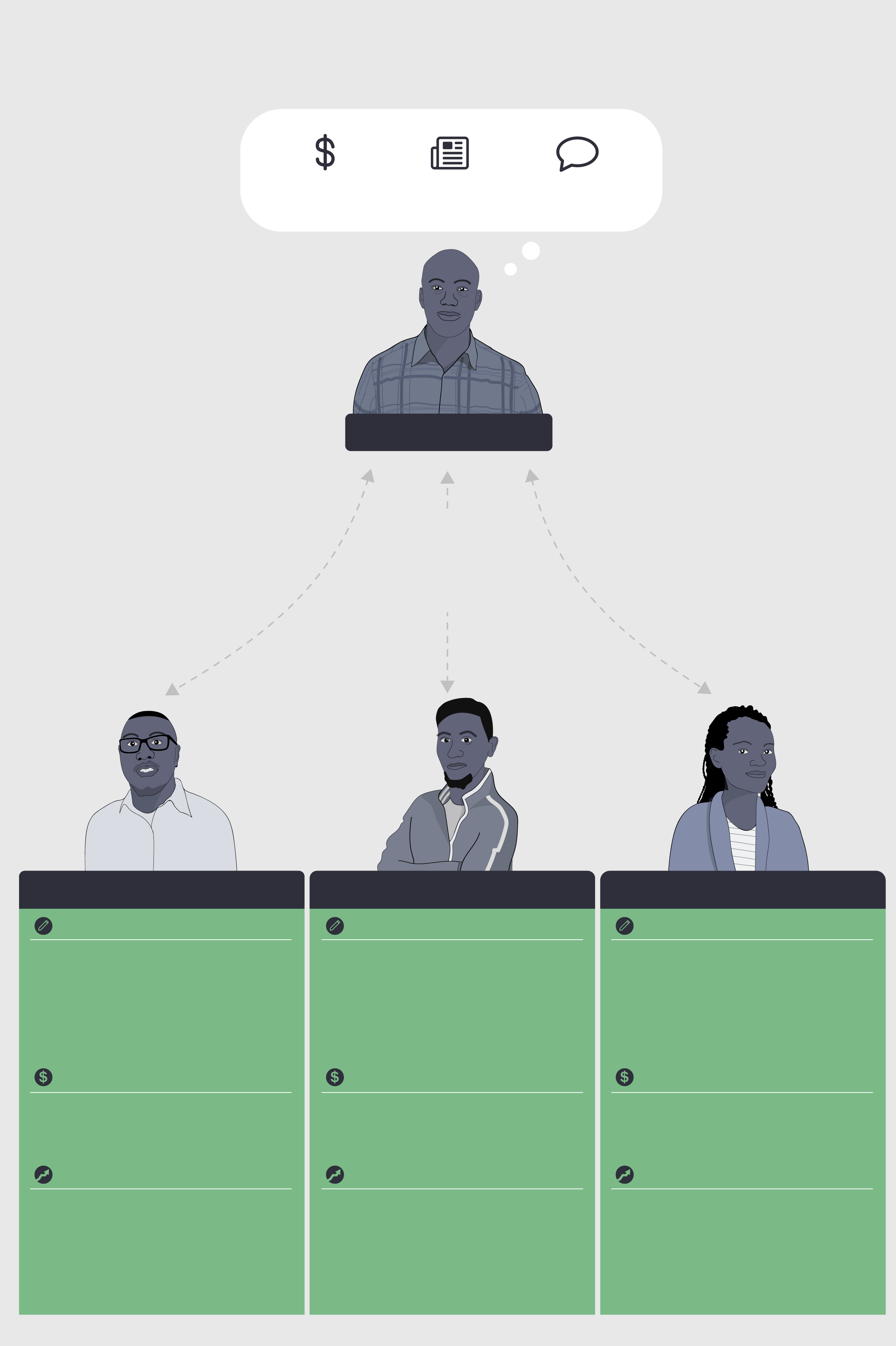

Kenyan journalists work in a politically sensitive context, often hindered by political and economic forces. The following graphic will introduce a few of these actors as “user personas,” which represent composite portraits of respondents. These four user personas demonstrate the pressures faced by Kenyan journalists and editors today:

Drivers of Editorial Decisions:

Political

Pressure

Competitive

Pressure

Financial

Considerations

editor

relationship:

relationship:

relationship:

In high-pressure newsrooms, editors have little time for their staff’s professional development.

Based outside of Nairobi, correspondents have largely transactional relationships with editors. They submit stories via email—with little editorial feedback or mentorship.

Freelancers rely on personal relationships with editors to secure pipelines for publishing work.

Local Correspondent

Staffer

Freelancer

Job Description

Job Description

Job Description

Based in the field, and expected to cover local news for 2-4 counties.

Their role as a key county watchdog is to be fluent in government policy and operations, but resource constraints make this difficult.

Work within the newsroom, but represent a small fraction of the staff.

They are expected to cover national events, and increasingly asked to produce more content with fewer resources.

Work for multiple media houses.

They are free to pick topics of interest and can theoretically dig deeper on a story, but financial pressures often preclude it as they’re not paid for research time.

Income

Income

Income

Contracted to a single media house, paid per story.

Employed by a single media house on a yearly salary.

Only paid for the stories and/or ideas they successfully pitch.

Paths for Growth

Paths for Growth

Paths for Growth

Often held hostage by time deadlines, which limits their ability to create “stand out” features or deepen subject matter expertise. These constraints lead to very few paths for growth.

Move up by keeping their heads down and remaining uncontroversial; this incentivizes self-censorship.

Deepening expertise in a specific subject area, and building relationships with more lucrative international media houses, offer potential for advancement.

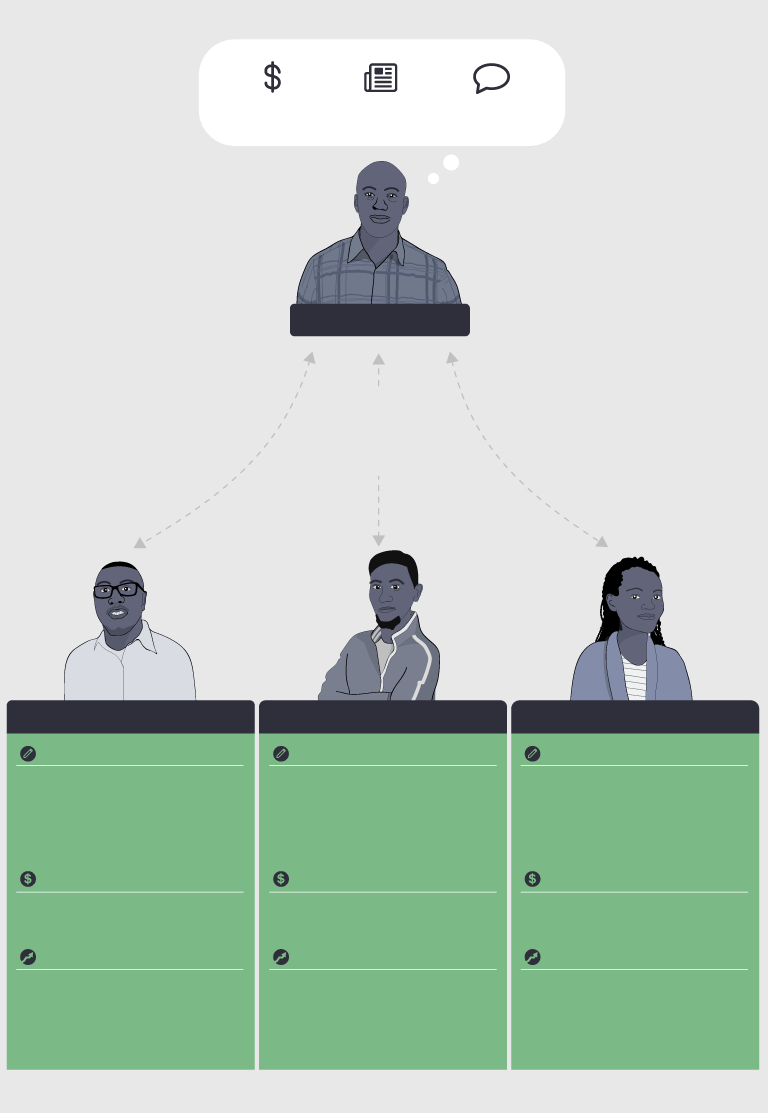

Drivers of Editorial Decisions:

Competitive

Pressure

Political

Pressure

Financial

Considerations

editor

relationship:

relationship:

relationship:

Based outside of Nairobi, correspondents have largely transactional relationships with editors. They submit stories via email—with little editorial feedback or mentorship.

In high-pressure newsrooms, editors have little time for their staff’s professional development.

Freelancers rely on personal relationships with editors to secure pipelines for publishing work.

Local Correspondent

Staffer

Freelancer

Job Description

Job Description

Job Description

Based in the field, and expected to cover local news for 2-4 counties.

Their role as a key county watchdog is to be fluent in government policy and operations, but resource constraints make this difficult.

Work within the newsroom, but represent a small fraction of the staff.

They are expected to cover national events, and increasingly asked to produce more content with fewer resources.

Work for multiple media houses.

They are free to pick topics of interest and can theoretically dig deeper on a story, but financial pressures often preclude it as they’re not paid for research time.

Income

Income

Income

Contracted to a single media house, paid per story.

Employed by a single media house on a yearly salary.

Only paid for the stories and/or ideas they successfully pitch.

Paths for Growth

Paths for Growth

Paths for Growth

Often held hostage by time deadlines, which limits their ability to create “stand out” features or deepen subject matter expertise. These constraints lead to very few paths for growth.

Move up by keeping their heads down and remaining uncontroversial; this incentivizes self-censorship.

Deepening expertise in a specific subject area, and building relationships with more lucrative international media houses, offer potential for advancement.

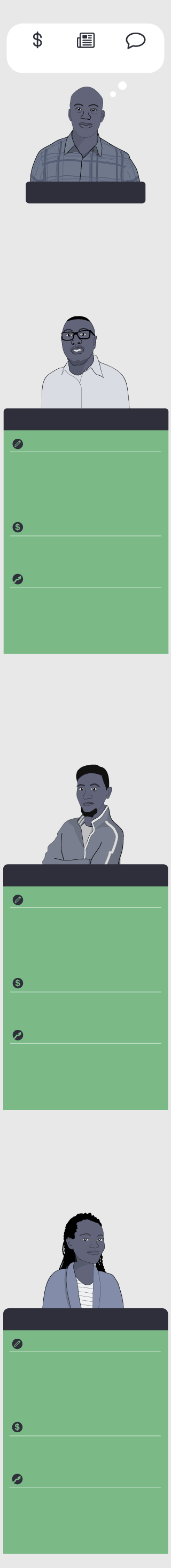

Drivers of Editorial Decisions:

Competitive

Pressure

Political

Pressure

Financial

Considerations

editor

relationship to editor:

Based outside of Nairobi, correspondents have largely transactional relationships with editors. They submit stories via email—with little editorial feedback or mentorship.

Local Correspondent

Job Description

Based in the field, and expected to cover local news for 2-4 counties.

Their role as a key county watchdog is to be fluent in government policy and operations, but resource constraints make this difficult.

Income

Contracted to a single media house, paid per story.

Paths for Growth

Often held hostage by time deadlines, which limits their ability to create “stand out” features or deepen subject matter expertise. These constraints lead to very few paths for growth.

relationship to editor:

In high-pressure newsrooms, editors have little time for their staff’s professional development.

Staffer

Job Description

Work within the newsroom, but represent a small fraction of the staff.

They are expected to cover national events, and increasingly asked to produce more content with fewer resources.

Income

Employed by a single media house on a yearly salary.

Paths for Growth

Move up by keeping their heads down and remaining uncontroversial; this incentivizes self-censorship.

relationship to editor:

Freelancers rely on personal relationships with editors to secure pipelines for publishing work.

Freelancer

Job Description

Work for multiple media houses.

They are free to pick topics of interest and can theoretically dig deeper on a story, but financial pressures often preclude it as they’re not paid for research time.

Income

Only paid for the stories and/or ideas they successfully pitch.

Paths for Growth

Deepening expertise in a specific subject area, and building relationships with more lucrative international media houses, offer potential for advancement.

Constituent 2: Government

The government has been, and continues to be, one of the media’s most determined opponents in Kenya. Kenya has a long history of political interference in media, applied through a wide array of control tactics. These range from laws and regulations aimed at limiting press freedom to cooptation, harassment, and even violence. For many respondents, however, the 2010 Constitution—which includes explicit protections for freedom of the press—fostered widespread optimism about the potential strengthening of media. This optimism was challenged, however, after the 2012 elections, which made Uhuru Kenyatta president. At the time, he was facing charges by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged involvement in violence following the 2007 elections that left over 1,000 people dead. As a result of negative press coverage, many respondents felt strongly that the Jubilee administration began targeting media actors with an increasingly aggressive zeal. Respondents believed that the Jubilee government implemented a strategic anti-press policy because it “blamed” the media [and CSOs] for the prolonging of the ICC trial.

Even after the ICC case was dropped, the Jubilee government did not relent in its efforts to undermine press freedom. A former reporter for KTN explained, “The government consolidated power after the Westgate [terrorist attack]. With Westgate, investigative reporting really helped the public understand what was happening. It was good for the public, but it was negative for the government because it exposed the corruption and the compliance of the army. It exposed how long the army let the attack unfold for. The government responded to this exposure by clamping down on security-related reporting. It first started as open threats to the media houses, then came out with a more refined communication strategy that both isolated reporters and then media houses.”

The conflict with the media was again recently evidenced when the current Jubilee government took four television stations off the air after they refused to comply with State House orders not to cover a mock inauguration by political opposition leader Raila Odinga.

How government pressures and incentivizes media

Every major media house in Kenya is owned by either a politician, a close party affiliate, or a business person with other commercial interests that depend on politicians’ good graces.

In its efforts to limit press freedom, the state has taken advantage of many tools, including, in some circumstances, violence and intimidation. In a recent report, Human Rights Watch and Article 19 documented a worrying trend of journalist intimidation. However, outright violence is not as common as the more-subtle tools of economic, legal, regulatory, and political pressure.

Political pressure

To varying extents, many Kenyan media houses have political entanglements, which influence their independence. Every one of the establishment media houses is owned by either a politician, a close party affiliate, or a business person with commercial interests that depend on politicians’ good graces. One civil society respondent believed “there is no distinction between politicians and media. Politicians or their cronies own the media, which is a big challenge. Corporations who buy advertising also have links to politicians and will exert pressure on the media.”

As owners wield influence over journalists’ and editors’ careers, politicians have been known to work their connections, resulting in a widespread sense of insecurity among journalists. “Politicians, particularly the ruling coalition, have influenced the removal of critical journalists from the newsrooms across various media institutions, hence depleting media of critical journalists,” according to one respondent working on press freedom issues. He went on to say “the government flags enemy journalists, and then pressures editors to punish, marginalize, or fire them.” Several recent, high-profile firings were cited as evidence, such as the firings of Daily Nation editor Denis Galava and cartoonist Gado.

Economic pressure

Government also wields economic leverage over Kenya’s media. As discussed earlier, the government has historically been one of the main sources of advertising revenue in the country; large corporations, primarily banks and telecommunications firms, are the other key sources. Some estimates place government advertising at 30 percent for the entire media industry. In a sharp departure, the government created the Government Advertising Agency (GAA) in 2015, which required all government departments to go through this agency before purchasing public advertisements. It then created its own advertising platform, “MyGov,” a website and newspaper insert, where government agencies would now be required to place their ads, in lieu of purchasing advertising from Kenyan media. While the Kenyan government claimed that this shift was for efficiency, many in media and civil society believe that this was intended to wield greater influence over private media houses. As a result, this policy has eliminated the media’s single largest sources of ad revenue.

Overall, the significant decline in ad revenue has cost thousands of newsroom jobs. The political influence of advertising also extends to corporate advertisers. A number of media respondents noted that corporate interests threaten to withdraw advertising if unfavorable coverage is published or broadcasted.

However, these new pressures are also driving media entrepreneurs to think creatively and experiment with new business models. Paywalls, online advertising, interactive web features, and social media were all cited as ways establishment media are trying to attract and strengthen audience engagement through online content. Media companies—both establishment and independent—have also launched efforts to strengthen fact-checking (Africa Check, The Nation’s Newsplex), to support investigative journalism (Africa Uncensored), and to crowdsource content for independent reporting (Hivisasa, The Elephant).

Regulatory and legal pressure

The 2010 Constitution marked a major turning point for media regulation in Kenya. The new constitution provided, under Section 34, the establishment of the Media Council of Kenya, an independent regulatory body tasked with setting media standards, and regulating and monitoring compliance with those standards. Subsequent laws—enacted largely after the Jubilee government assumed power in 2012—have, in essence, undermined the independence of this body. The 2013 Media Act, a revision of a 2007 act by the same name, weakened the Council, which must look to the state for core support while trying to maintain its independence.

Further amendments to the law, under the Information and Communications Act of 2013, created two other regulatory bodies with more authority to intervene in the media: the Communications Authority and the Multimedia Appeals Tribunal. Unlike the Media Council, these institutions are not independent of the state but their roles duplicate the core functions of the Council.

Attention has been drawn to the Tribunal’s role in hearing complaints against journalists and media organizations, although this falls within the Media Council of Kenya’s purview. It is however, the hefty fines of up to approximately USD 20,000 for individual media houses, and approximately USD 5,000 for individual journalists, that are most problematic. In a bid to avoid such severe penalties, media institutions and individual journalists are likely to self-censor or completely drop stories deemed politically sensitive. For many respondents, the creation of additional regulatory institutions is a deliberate effort by the state to create confusion within the regulatory regime and exercise greater control over the country’s media.

Legal action by government officials against media organizations has been another strategy for attacks against the press. The threat of lawsuits hangs over media houses. One respondent joked that journalists are trained in “how not to get sued.” Another journalists noted that “the fines are beyond the budgets of many media houses, especially independent media, bloggers, or online news sites.” Fortunately, respondents generally reported faith in the independence of the courts. In February 2018, the courts demonstrated this by ordering the government to allow four television stations back on the air after they had been forced to stop broadcasting following their coverage of the mock inauguration of opposition politician Raila Odinga. It was several days, however, before the government complied with the court’s orders.

How media copes

In response to political pressure, media organizations opt between the risk-mitigating strategy of self-censorship or directly confronting government interference. The latter path—resisting government pressure to publish stories that hold the powerful to account—runs serious risks. Despite this, some have been testing new tactics to protect themselves, while ensuring critical coverage reaches the citizens who need it.

Standing in solidarity

"Media needs to create strong solidarity networks. Politicians are very good at isolating and attacking media houses."

Journalists have been experimenting with approaches to temper risks to their career or wellbeing. Solidarity has emerged as an important strategy. An establishment media columnist explained, “media needs to create strong solidarity networks. Politicians are very good at isolating and attacking media houses.” Staff reporters, editors, freelancers, and correspondents counter by organizing collective opposition to government efforts to stifle freedom of the press. This includes speaking out together when the government targets individual journalists or media houses, and sharing tactics for political pressure. For example, one tactic for bringing critical coverage to the public is to have journalists pass along promising leads to a colleague to make a story public if they themselves feel unable to publish it. They may also circulate leads to many journalists, encouraging widespread coverage of an issue and making it difficult to retaliate against a single journalist in response—a practice one respondent described as “spreading the risk”.

An illustrative case is the coverage of two massive corruption scandals that demonstrate the importance of widespread coverage of sensitive issues to force government action: the National Youth Service (NYS) scandal in 2015 and the Afya House (Ministry of Health) scandal in 2016. In the former, close to USD 2 million was lost through a scheme that involved misuse, diversion, and siphoning of public funds related to the NYS. As a result of the scandal, Anne Waiguru, the cabinet secretary in charge of the Ministry of Devolution and Planning, which oversees the NYS, was forced to step down. (She later contested and won the governorship of Kirinyaga County in August 2017.) In the Afya House scandal, close to USD 5 million went unaccounted for after an internal leak showed massive theft of public funds. As a result of the scandal, 30 health officials were “re-deployed.”

Both scandals involved individuals close to Kenya’s top political leadership. Given the sensitivities, media reporting was, in some cases, over cautious. Some respondents, particularly in regards to the NYS scandal, felt the media had failed to maintain sustained pressure. At the same time, in both cases, the government felt compelled to take public action in response to the negative publicity it was receiving.

Efforts at creating solidarity networks to challenge political interference exist to some degree. Journalists are, for example, represented by several different organizations—the Kenyan Union of Journalists, the Kenyan Correspondents Association, the Association for Freelance Journalists, the Association of Media Women in Kenya, and the Bloggers Association of Kenya—with varying degrees of success. In addition, there are initiatives such as the Kenya Media Sector Working Group, a coalition of like-minded civil society organizations with an interest in media and press freedom, convened by UNESCO Kenya.

The Kenya Editors Guild (KEG) has also, in recent times, become vocal in cases where the state has threatened the journalists’ right to report. Recently, KEG put out a strongly worded statement in response to the government’s threat to punish journalists and media houses that covered NASA leader Raila Odinga’s mock swearing-in ceremony in January 2018. The statement—signed by KEG Chair Linus Kaikai, a senior editor at the Nation—apparently upset the state. In the days that followed, police blocked The Nation Media Group’s entrance for two days, seeking to arrest Kaikai and two other journalists. A Kenyan court then issued an order barring police from arresting them.

Despite the existence of these efforts, many respondents noted that these networks could be strengthened.

Calling out government intimidation

Journalists are also experimenting with ways to hold government to account for its attacks on the press. Some respondents shared stories of successfully subjecting government to widespread public criticism. Journalists who have been threatened by political actors will sometimes respond publicly to those efforts by naming the individuals who are issuing threats. In doing so, journalists can draw public support, and rally other journalists in solidarity. A former managing editor explains, “There has always been a danger to journalists. Good journalists are aware of the risks and don’t care. But if you are in danger, you need to spread the word to slow the government’s momentum. Make it public, name and shame, don’t pull punches.” A recent report by Human Rights Watch and Article 19, “Not Worth the Risk: Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections,” is one example of an effort to draw attention to the risks journalists face, and to those that threaten them.

Defensive coverage

On the other hand, many newsrooms have adopted a culture of self-censorship, softening their coverage or avoiding topics that could draw the negative attention of political interests. Many engage in shallow reporting, often simply repeating the official government line in an effort to protect themselves. As one establishment reporter explained, “Journalists need to calibrate, to be more cautious. There is an unwritten rule that they need to know all the interests in a story and weigh those interests carefully when deciding to report.” A respondent with The Standard noted that while the Moi family, which owns the Standard Media Group, rarely gives explicit direction to editorial staff, they frequently censor themselves over issues perceived as upsetting ownership. For example, he cited sensitivities covering the candidacy of Gladys Boss Shollei, the wife of then Standard Media Group CEO Sam Shollei, for women’s representative in Uasin Gishu County. Failing to self-censor, on the other hand, can lead to retribution. One journalist recalled that he was let go over after reporting on alleged corruption within the National Youth Service.

Accepting pay for coverage

Government pressure combined with low pay among journalists, particularly correspondents and freelancers, has also created perverse incentives for “pay-to-play” journalism. A journalist or editor might receive a one-time or regular payment in return for favorable coverage. Some journalists are even on retainer by politicians, the state, and political parties to ensure positive press. One civil society respondent noted, “The government strategy is to co-opt journalists. The president has had [many] campaign stops but has not allowed local journalists to cover his campaign events. Instead it is his ‘press corps’ who are paid to cover his campaign favorably. Local journalists try to cover them but end up just parroting what he says. They will also go as far as to self-censor, and to give preferential coverage in the hopes of being favored next time to secure access.”

A study by the Media Council of Kenya found that, “83 percent of the journalists interviewed noted there is rampant favoritism among editors in selecting stories to be published.” “Editors,” the study goes on to say, “are most likely to air political stories that come with brown envelopes.”

Constituent 3: Citizens

Citizen demand for news may be one of the Kenyan media’s greatest advantages. Kenyans consume a large quantity and wide variety of information and media. According to the Kenya Audience Research Foundation (KARF), “Out of the 24.7 million Kenyans aged 15 years and above, 19 million consume media on an average week.” Of the 16 million daily media consumers, KARF reports that 94 percent use print, radio, and television, and 33 percent access media digitally.

How citizens pressure and incentivize media

Kenyans may trust the media more than they trust the government, but this is a very low bar.

Every respondent in this study expressed some level of frustration or mistrust of media—a finding consistent with research by Afrobarometer that found only 39 percent of Kenyans “trust the media a lot.”

Low trust in media

Respondents were aware of the political relationships of the owners of establishment media organizations (see Constituent 2), and believe that these relationships influence coverage. This is a key driver of mistrust. To illustrate this, a university student explained, “Media in Kenya is not independent. [I know] because of the way the media houses report the news. Citizen TV, for example, changed its colors to be close to Jubilee.” In fact, most citizen respondents believed media houses to be politically aligned. Another student said, “Media is run based on the business interest of somebody. We see the media houses who are either pro-left or pro-right. You can see how they cover stories. You also see self-censorship.”

Media respondents were acutely aware of this perception. One editor noted that “covering politics is tricky. If you attack one side, you are branded as supporting the opposition.” One strategy, described earlier, is to run an equal number of stories or columns perceived as pro- and as anti-government. However, despite the efforts of some editors to overcome these perceptions, respondents felt strongly that Kenya’s media retain strong partisan bias. This feeling was reinforced by the well-known political relationships of media owners, and the belief that ownership strongly influences the types and angles of stories produced. These perceptions are also reinforced by the public’s awareness that journalists are paid to write favorably about public figures.

Relying on social media

Internet usage estimates vary considerably in Kenya, from 26 percent, reported by the International Telecommunications Union in 2016, to 90 percent, reported by the Communications Authority (CA) in 2017. Despite the CA’s highly optimistic estimation for internet users, social media use remains considerably lower across the country as a whole. Across Kenya’s 48.5 million people, recent estimates suggest there are approximately 7 million Facebook users, 10 million WhatsApp users, and 2 million Twitter users. Nevertheless, in Nairobi, where social media usage is most concentrated, all three are important channels for accessing and triangulating information.

Many respondents expressed understanding of the potential for misinformation online, a finding backed by a recent poll which found 90 percent of respondents reported having seen false or inaccurate news in relation to the general election. As one journalist said, “Digital has really impacted the newsroom. It has changed how people get news. But it has also empowered the purveyors of fake news.” On one hand, some people believe that online conversations are fast, diverse, and resilient enough to challenge rumor, and surface the truth. However, others expressed the opposite opinion, calling Kenyans “uncritical,” too quick to share news without evaluating it. There is truth to both statements. Social media is valuable in spreading news, but the risks of rumor mongering and manipulation are also real.

Triangulating information from multiple platforms

While there may be many factors, citizen respondents frequently noted that they rely on multiple sources for information to balance the perceived bias in media. By looking at several media outlets, they hope to gather multiple angles, understand the potential biases in individual pieces of coverage, and identify stories or details that have been entirely omitted. As one University of Nairobi student noted, “You just need to be smart and check multiple sources to not fall into the trap of fake news… If you watch one channel for long, you have a skewed mindset on certain issues and that is why it is necessary for us to watch as many channels so as to have a broad view of information from various sources.”

Kenyans triangulate information through multiple outlets and across multiple mediums. They will read newspapers, watch television, and listen to the radio. Friends and family are an important source of validation, and social media has made it significantly easier to access, share, and validate information. Multiple audience respondents discussed the fact that they “trust” social media, because they trust their friends and family, who share information and engage in conversations with them on those platforms. Across the board, respondents most widely referenced using WhatsApp groups to monitor and share news with friends, colleagues, and family. Facebook and Twitter were also commonly cited, though the former more so.

How media responds

Cumulatively, through an appetite for news and information, and especially through a passion for social media, citizens in Kenya today are putting pressure on the national media industry to innovate and improve its work.

Covering stories that break on social media

"Online is dominating breaking news. Media has become something of a curator as opposed to news breaker"

The pressure of social media, where news breaks more quickly, is also putting competitive pressure on traditional media organizations. Almost all media respondents noted that breaking news has become the domain of social media. Events that Kenya’s news media would have traditionally been the first to present to the public are being “scooped” online. Without the ability to break news, journalists feel that their relevance has suffered.

As a result, social media is pushing establishment media to think more strategically about its competitive advantage in an environment where it can no longer break news. “Online is dominating breaking news. Media has become something of a curator as opposed to news breaker,” said a civil society respondent working on digital policy and advocacy. Another respondent working in digital news argued that, with the loss of their breaking news function, his organization is focusing on adding value through fact-checking and more in-depth reporting to ensure news circulating online is credible.

The rise of digital has also helped to “democratize” Kenya’s information ecosystem. Establishment media no longer have a monopoly on information. Some stories that might otherwise have been censored, self-censored, or ignored by the establishment media accordingly gain traction online. Researchers frequently heard that stories generating attention on social media can, in turn, compel establishment media organizations to also extend coverage. For example, in June 2017, 30 people were rushed to the hospital after a cholera outbreak at a hotel in Nairobi. Because the hotel was affiliated with a prominent politician in the Kenyatta administration, some respondents believed the outbreak would have been ignored if not for social media. (The story was eventually covered critically in establishment outlets, including The Nation). Without the presence of social media, there would be less pressure on establishment media to report on sensitive topics.

Shifting to digital platforms

Journalists have had success publishing content digitally, circumventing the constraints of establishment media organizations, and reaching citizens directly. “Apart from expanding the democratic space, digital is also largely inexpensive to start and operate. One does not, for instance, need a lot of money to invest in the establishment of a website. In many instances, digital spaces enable the publication of public interest stories that normally will not come through mainstream media,” explained an editor with The Nation. A handful of promising digital-first publications were referenced by multiple respondents as examples of the growing diversity of the media landscape. For example, Owaahh and Gathara’s World were cited as outlets for thoughtful reporting and analysis, and Hivisasa and The Elephant were noted for their diversity of contributors and viewpoints. The Reject and the Kenyan Women, both produced by the African Women and Child Feature Service, were noted for surfacing underreported stories, with a focus on development and women’s issues.

A number of media sector respondents acknowledged the importance of bloggers in covering stories censored by establishment media houses. Publishing independently online liberates journalists from the political pressures of ownership (although not government intimidation), with lower startup costs than printing a newspaper or operating a radio station.

Innovating digitally

Many outlets are struggling to adjust their business and reporting models in response to pressure from social media and online advertising. All media outlets are struggling to earn money from their websites. Online ad sales have not replaced the decline in revenue from print ad sales. And, like most media companies globally have had to contend with, audiences are increasingly accustomed to free content. Nevertheless, respondents working at establishment media houses frequently discussed the importance of having a strong digital presence, as more and more consumers come online. One respondent discussed expanding the newspaper’s digital presence, and incorporating online video and interactive storytelling methods. As another example of digital innovation, a local media site, Thika Town Today, uses WhatsApp and Facebook to connect more closely with its audiences, by crowdsourcing story ideas and facilitating conversations about local issues.

Constituent 4: Civil Society

Like the media, Kenyan civil society has a history and reputation for being relatively robust and professional. Also like the media, civil society is working in a shrinking civic space, with decreasing support from donors, and under pressure from the Jubilee administration. For example, in 2015, the Kenyan government froze the banks accounts of two Mombasa-based organizations, Muslims for Human Rights and Haki Africa, which had been critical of the government’s anti-terrorism policies. (A Kenyan court subsequently ordered that their banks accounts be unfrozen.) In a more recent example, after the August 2017 election, Kenya’s NGO regulator attempted to shut down two human rights organizations involved in election monitoring.

A strong, symbiotic relationship between civil society and the media is one of the most important potential connections in Kenya’s accountability ecosystem. While it is the media’s role to shine a light on issues of public interest, it is civil society’s role to translate that information into policy change, by engaging government and mobilizing citizens. Highlighting the power of cooperation, a veteran freelance journalist said, “Media plays a role that goes beyond CSOs. While CSOs can lobby and negotiate with government, media has the power to pick the issues that people focus on.” In Kenya, there is an opportunity to strengthen the connection between these sectors by highlighting their similar challenges and their aligned governance goals.

How civil society pressures and incentivizes media

CSOs are well aware of the need to have productive relationships with media. They need these relationships to draw the public’s attention to the issues they work on. They also need these relationships to ensure that these issues are presented accurately in the press. However, considering the current divide between CSOs and media cited by several respondents, to realize the potential of these relationships, CSOs need a greater understanding of how media works and how to engage them.

Facilitating human interest content for journalists

When Kenyan CSOs and media cooperate, they both benefit. One journalist called NGOs and CSOs “great links to story ideas.” Another respondent who participated in a civil society-facilitated gender training described it as transformational. This training successfully sparked debate, helping important gender issues resonate with the (largely male) audience by encouraging them to relate the topic to their own female family members. To this particular respondent, civil society trainings must be personal and compelling. When they are, she went on to say, they can transform the way journalists think about and cover social issues.

Another CSO respondent described the story of a health facility, which was put at risk due to a “land grab” by government officials. Within a few hours of hearing the news, the CSO organized a demonstration via WhatsApp with hospital patients. They simultaneously organized a press briefing in Nairobi for media. This successfully drew the attention of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, and within three weeks, the land was returned to the health facility.

Confusion and mistrust

On the other hand, CSOs and media need to overcome mutual mistrust. According to a former Standard journalist, now working in civil society, “Media holds the view that CSOs cannot be trusted. CSOs think media is weak and influenced.” The sectors primarily interact with each other through personal connections rather than institutional relationships.

Outside of personal connections, CSOs and journalists relationships are weak at best. This mistrust seems to be driven by frustration among CSOs that media appear uninterested in covering issues CSOs work on, and on the other side, that CSOs fail to make their issues compelling and newsworthy. Researchers also heard concerns from CSOs about the need to pay for coverage. One CSO respondent noted that “Media always want sensational stories, and think the development issues can wait until tomorrow.” A sympathetic civil society respondent acknowledge that his peers needed to take greater responsibility in getting their issues into the media saying “CSOs complain about media, but their events are not newsworthy. CSOs need to prove [our issues] are newsworthy.” Overall, limited understanding of each sector by the other seems to underpin the trust issues that have hurt cooperation. Improving communication and understanding between CSOs and journalists, including developing CSOs’ media outreach capacity, could help to begin bridging some of these gaps and establishing stronger, more productive relationships.

Kenya’s independent media is ripe for a new era of investment. Changes in advertising and the rise of digital and social media alone are enough to spur shifts in the media industry. But Kenyan media face additional powerful political and economic forces, which underpin the need to find creative strategies to enhance media’s independence. Declines in revenues have led to the downsizing of newsrooms, and an accompanying downgrading of capacity. Many journalists have been left without sufficient pay and job security, which has made them economically vulnerable. At the same time, the Kenyan government has demonstrated its willingness to exercise a range of tactics—economic, regulatory, legal, and political—to minimize critical coverage and restrict press freedom.

Fortunately, there is an appetite for trustworthy, rigorous journalism among Kenyans. There is also a talented pool of journalists who, with the right support, can deliver high-quality, in-depth reporting. At times, the Kenyan media has demonstrated its willingness to cover issues of public importance, no matter how sensitive or controversial. Digital media has also significantly reduced the costs of publishing and disseminating information, freeing independent journalists from the whims of a small number of decision makers who control the media establishment.

To overcome the many forces described in this report, an array of complementary strategies are necessary. Investments need to be made in developing the capacity of journalists to produce high quality, in-depth reporting that meets international standards. Such investments may range from training in journalistic basics (e.g. abiding by journalists’ codes of conduct, addressing issues of bias in reporting) to building an expert cadre of investigative journalists. Connecting journalists more closely to civil society can help them access the latter’s expertise on issues ranging from health to finance to government. In turn, this can increase the ease and ability of media to cover issues of public importance.

Perhaps more challenging will be finding creative solutions to shield journalists and independent media from direct government intimidation and influence. Nevertheless, there are options that can begin to mitigate the impact of the government’s many carrots and sticks it wields against Kenyan media. Supporting new or existing independent platforms for publishing content free of political interference can help reduce the dependence on establishment media, who face constraints on their independence from government. Paying journalists fairly can help mitigate their dependence on “brown envelopes.” Strengthening solidarity networks among journalists, and empowering these neworks to advocate for press freedom, can help challenge government attacks on media and journalists.

In the following section, we offer a few signposts on the way to this ambitious goal.